Paul Tillich writes, in his Systematic Theology: “A group, whether a family or mankind as a whole, does not participate in the effects of the New Being.” (I, 87) The family is meaningful, but it is not a Christian value—it is no ultimate.

It is remarkable that, in the history of Christianity, one of the simple truths pervading the New Testament, early monastic literature, the Church Fathers’ writings, medieval scholastic and mystical traditions, up to early modern times, has found itself subverted and turned into its contrary in modern times. The simple truth is that throughout history, the ideal of Christian life was an ideal of renunciation, prayer, spiritual ascent, and assimilation to Christ. The subverted, transformed truth is that family is the central Christian value, and that religion depends on the construction of family relations in the world.—How did we get here?

In the second and third centuries of our time, during the formation of Christian communities and the onset of monasticism in Syria, we find a salient example of how early Christian ideals were thought of in both theological and social terms. Arthur Võõbus writes, in the first volume of his History of Asceticism in the Syrian Orient, that early Syrian Christians upheld ascetic ideals that were exclusive of any kind of commitment to the family, social groups, or other constellations of people. Great emphasis was placed on the ideals of virginity and continence, to the point where Christian perfection became indistinguishable from abstinence from marriage and procreation. Sexes were invited to live separately to preserve their virginal integrity. Procreation was thought of as a distraction from prayer and devotion: being surrounded by children makes it difficult to remain focused.

The early testimonies collected by Võõbus do not appear original at all when one considers the unmistakable injunctions of the New Testament. When Christ states that the Kingdom of Heaven is for the eunuchs and prostitutes, when he says that mother, father, and children will turn against each other, and when he calls the apostles to follow him without turning back, these statements easily give way to a literalistic interpretation: that family bonds have no relevance and that they do not “participate in the effects of the New Being,” as Tillich writes. Hence, early Syrian Christianity is not a case of gnostic eccentricity. Rather, it is an early example of how the Gospel may be understood as applying to the concrete relations in which one might intentionally or unintentionally engage. The aim of mankind does not lie, according to those early monastic interpretations, in the construction of immanent social networks, such as family, but outside mankind and any such construction, in the “Kingdom of Heaven.”

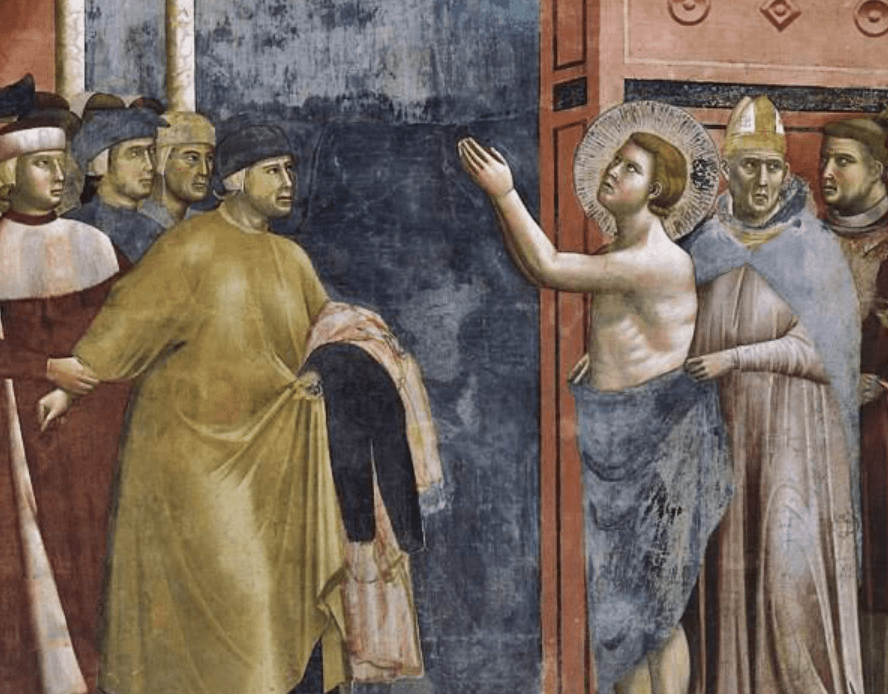

These ideas did not remain geographically or culturally restricted to the East. Even Greek documents such as Apophthegmata Patrum and hagiographies of the time are full of stories in which children reject their families to dedicate their life to monasticism and asceticism. Evagrius Ponticus, the greatest of the Desert Fathers, is said to have replied, to the news of his father’s passing, that he only has one Father, the Father in the Heavens. As harsh as this story may appear to contemporary ears, it shows that the injunctions of the New Testament were not understood as mere metaphors. One who followed God was one who renounced everything else.

It is significant that the decline of ancient asceticism coincides with the rise of political theology under Justinian. When Origenism was condemned in 557, when the ideal of ascetic life and bodily renunciation shifted toward the stabilization of imperial order, theology became deficient, and the era of early theological audacity ended.

Nevertheless, the monastic and spiritual ideals continued to flourish throughout Eastern and Western Christianity. With the onset of late medieval devotio moderna and mysticism, we even see a restoration of ancient ideals, the creation of new religious communities, and a revalorization of virginity and renunciation. In late medieval literature, Ruysbroek, Tauler, Eckhart, Thomas a Kempis, we would seek any emphasis on filial piety or the importance of family in vain. The goal of religious life is not to accumulate relationships but to remain free from any engagement outside Christ.

The origin of Christian family values lies in the nineteenth- and twentieth-century economical growth of the West. The industrial revolution made wealth easily accessible, without the restrictions of premodern aristocracy and class. Western, traditionally Christian societies turned into pluralities of family nuclei, potentially expendable under the impulse of material wealth, without the prerequisite of nobility or social status. The class system of premodern societies was subverted by an economical system; the transcendent valorization of individual devotion turned into the immanentistic valorization of wealth. Or, to use Max Weber’s words in Die protestantische Askese und das moderne Erwerbsleben, premodern Catholic Weltflucht was supplanted by the mundane asceticism of labor.

When the bourgeoisie wanted to see its wealth and the principle of its dominating position in society consecrated, bourgeois values erupted in Christianity. Families became an object of interest to Christianity because the society on which Christianity depended had transformed into a society of wealthy families. Suddenly, it became a religious value that a woman obeys her husband, that children are submissive to their parents, and that, like in the Old Testament, the father begets many children. The process was not of theological nature, and Max Weber’s historical narrative of the supersession of Catholicism by Protestant mentality seems to invert the order of things: The bourgeoisie was not motivated by Protestant work ethics, but it simply gave in to the temptation of abandoning the spirit of ascetic self-perfection to adopt capitalistic enjoyment of wealth instead. The incorporation of this mindset by Christian theology is a consequence of this social shift rather than its cause.

Early Christians thought of Christianity as a road paved with virginity, continence, renunciation, betrothal to Christ, and contemplation. The bourgeoise thinks of Christianity as a tool to maintain its social status and enjoyment of its wealth, to stabilize the system from which it benefits, and to populate the world with a dominant class that perpetuates the bourgeois identity.

It is astonishing to think that the collective will to maintain bourgeois identity has managed, over the course of just one century, to give Christianity the shape of a family religion. It is even more astonishing that Catholic and Orthodox churches have actively contributed to that shift by focusing their whole theology on the family, the children, and the parents. Apart from Paul’s sapiential recommendations and echoes to the Old Testament, there is not a trace of these values in the New Testament. The representation of Christ’s family is full of hiatuses, incomprehensible interactions, misunderstandings and silence. Early monastic literature recommends never having children because of the distraction from God they represent. Medieval scholastics are utterly disinterested in theorizing about the family. There is no Christian document before the nineteenth century suggesting that family ought to be seen as part of religion. And yet, here is the West, evangelical Americans, traditionalist French, German, Italian, Polish, and Spanish Catholics, even Catholics in the East, advocating family values as the very core of Christianity. Christ called the son and the daughter to turn their back on their parents and to imitate him: and here are the sons and daughters proclaiming that the bourgeois family, the lack of sympathy for the poor and the immigrants, and the accumulation of wealth are Christian values.

Being part of a family or rejecting family; having children or refusing to have children; founding a family or remaining alone–these are choices that one makes outside religion. Premodern Christian theology does not say anything about these choices. Supporting the bourgeois endeavor to maintain traditional social constructions is not a Christian ideal. The “New Being” is achieved through assimilation to Christ alone.

Leave a comment