οὐ δεῖ παραδόσεσιν ἀνθρώπων ἀκολουθεῖν ἐπ’ ἀθετήσει ἐντολῆς Θεοῦ (Basil the Great, Moralia XII, 2)

How is it possible that Christianity, a Galilean insurrectionary movement fighting against political oppression and religious corruption through spiritual transformation, has turned into the political ideology of a dominantly Western, conservative, and right-winged population? What is the historical development that led from a group of late antique anarchists (according to A. von Harnack) to the image of a religion that, in its Western inculturated form, has supported totalitarian, reactionary, and dictatorial states, and displayed, in its most radical forms, anti-social, sectarian, and downright misanthropic behaviors? Why is a small group–the self-proclaimed “traditionalists”–inside of a large Church–the Catholic Church–allowed to take this behavior to its utmost extreme, advertise an agenda of pure and exclusive ritualism, in total contradiction to the essence of what Christianity originally was, and present itself as the highest and only adequate realization of that essence? How can that group exist in a total opposition to the globalized context of our time, deny the dominating concerns of that context, and, instead of adopting the original Christian gesture of humble self-sacrifice, oppose social and politic development through uneducated, openly Pharisaic rigorism? How did we get to this point, where, in the face of increasing violence against women in all parts of the society, the image of Christ protecting a woman from a violent mob, does not inspire Catholics to take part in the fight against that violence, but drives them to shame victims of sexual violence, and prevent them from accessing medical care? Why, in sum, is nobody telling traditionalist Catholics that they got everything wrong, and that their complete lack of familiarity with the history of Christianity is the cause of their lack of understanding of what Christianity should be, today?

In the first volume of his work Church History of the Three First Centuries, German theologian Ferdinand Christian Baur lays out two models of the Church. One model is the one that he takes to be the original and adequate realization of the Church. It is the Church as a living entity, that evolves over the course of history, and progressively realizes the idea that Christ deposited in it. This model rests on the idea that God is so transcendent, so different from the world he created, that we cannot just express his essence in a singular truth or statement. Even the truth that he revealed to mankind through Christ is not a truth that we could just grasp and communicate to others. It is infinite. Limiting it to a certain ritual, language, ideology, or anything resembling a human tradition–Basil’s παραδόσεις ἀνθρώπων–would be idolatrous.

The other model is that of absolute revelation inside the world. This model presupposes that God has revealed himself fully and comprehensively at a certain point in time. Christ ordered the apostles to be the ministers of this revelation, and from their ministry emerged a continuous doctrinal and sacramental tradition. The tradition contains the full and articulated truth about God, and its form is invariable. In this respect, it is comparable to the Law given to Israel in the Old Testament. The only possible stances on tradition are sticking to it, or questioning it; accepting it, or rejecting it.

The second model is the traditional and conservative Catholic point of view. It became prominent in the second and third centuries of our time, when the first dogmatists, Irenaeus, Hilary, and Tertullian, identified the rise of Gnosticism as a menace and thought that it was necessary to counteract that menace. To oppose Gnosticism and its audacious speculations, they promoted the idea that being a Christian depends on one’s commitment to a certain authoritative, sacramental and theological tradition, i.e. the idea of apostolic succession. Tracing back the authority of the episcopal function and the validity of “official” theology to the apostles is a way of safeguarding these elements without having to justify them systematically, on theological grounds. Insisting on a tradition and on a line of successors by which the “original” teaching was preserved made it possible to legitimize ecclesiastical structures and teachings in the eyes of the Christian communities. One can be a true Christian only by adhering to apostolic doctrines. Departing from the content of that tradition is equal to departing from Christian faith.

As Adolf von Harnack showed in the first volume of his Lehrbuch der Dogmengeschichte, the idea of such a tradition is problematic insofar it is evident that it depends on the dynamics of the second and third century rise of new, speculative intellectual movements and scriptural hermeneutics. There is simply no evidence whatsoever for the reality of apostolic tradition outside the recommendations given by first and second-century writers, such as Ignatius of Antioch, against the inclusion of Gnostics and other groups of non-conformist believers, in Christian communities. The documents considered as apostolic, such as the Didache or the Apostolic Constitutions, were not written by the apostles, and there is no writing attesting that the apostles handed down functions and teachings in a codified and rigorous way. A vision of the Church that bases itself on the notion of apostolic succession makes itself vulnerable to historical criticism, and cannot but fail to properly respond to that criticism.

One could even go a step further and say that there is no Christian tradition. The New Testament did not invent new mythologies. Its mythological framework–the ideas of Heaven and Hell, the Last Judgment etc.–are borrowed from Jewish and Old Testament tropes. Its language is that of Helleinism and the Septuagint. Its concepts, in particular those that we find in John and Paul, come from Medioplatonic and Jewish philosophy. Early Christianity drew on the spadework done by different civilizations, and apart from the moralism of the Sermon on the Mountain, John’s speculation on the Logos and the divinity of Christ, and Paul’s universalist claims, it had very little originality. The only event on which Christians could build to constitute their own ritual identity was Christ’s eurachistic prelude to his passion. And even this event is consigned in just a few lines in John, Paul, and Justin the Martyr. The core values of Christianity are not traditional. They are living values that need to be adjusted to each new historical and cultural context.

Is this lack of originality a sign of literary or religious poverty? Does it make Christianity an unimaginative religion? Certainly not. Christianity started with a prosaic and unromantically austere idea: the overcoming the limitations of finite existence and the reconciliation with God. The realization of this idea requires faith in Christ. Christ has overcome sin, and mankind can participate in this overcoming through faith. This idea it neither intellectual, nor ritualistic, nor esthetic, nor a starting point for tradition–it is a religious-cum-historical, messianic fact. The richness of Christianity is by no means commensurate to its artistic, ceremonial, or intellectual originality. The incentive that it offers is moral and supernatural. It teaches to behave in a certain way and not to expect any finite benefit in return. The framework of that incentive is sacramental. If one follows the moral path of religion, one may participate in the celebration of divine mysteries. But the shape of those mysteries is, compared to moral obligations, accidental. There is no sacred language or vestment–the only human quality susceptible of sanctification is righteous behavior.

In the light of these plain facts, it is depressing and unnerving to see traditionalist Catholics in the US mindlessly repeat the same meaningless ideas: “TLM” (“traditional” Latin mass) against the “novus ordo,” communion by mouth and not by hand, celebration ad orientem, neo-Thomism. With these ideas, we enter an imaginary world, the figment of Western minds in quest of a new identity, the invention of people who, cut off from any source of cultural inspiration, populate their spiritual emptiness with caricatures of a tradition that has never existed. We see accidental features of Christianity suddenly becoming important, and the essential values of Christianity erased under the impact of a distressing lack of education. We see that one of Protestantism’s most popular commonplaces, that is, that Catholicism is Christianity for Pharisees, is becoming reality in the most alarming way.

Latin is a neglectable language, and if it had never existed, the Roman Catholic Church would not lose anything. It is a historical coincidence that Latin has become the language of Catholicism. Christianity is not a Western religion, it is the religion of people who spoke Aramaic, Coptic, Syriac, Ge’ez, Armenian and Arabic. It has spread to the West and, as in these Near Eastern and North African contexts, it has flourished in Western, Greek and Latin languages. It has served as a tool for poetry and theology, and, when used in liturgy, it evokes the depth and timelessness of Christian dogma. But the aim of its use is instrumental. It cannot have any other significance than a symbolic one.

Liturgy is not a monolithic product resulting from two millennia of ceremonial refinement, as if theologians had made collective and combined efforts to work on a unified result. It is an accumulation of historical strata, of which some have practical reasons, such as the use of the maniple, some other ones coincidental, such as the reading of John’s Prologue at the conclusion of every celebration, and other ones reasons of theological and ideological differentiation, such as the use of unleavened bread. Liturgical variations are not limited geographically and historically. There is not a single valid theological reason to give preference to sixteenth-century conventions articulated in the context of a Roman Catholic council. Liturgy in Ethiopia, Egypt, Syria, and Palestine is as Christian as any other mass, in Latin or vernacular language, in the West.

Thomas Aquinas is a partner for dialogue and not the exclusive teacher of Catholicism. Neo-Thomistic exclusivism was born with the intellectual decline of the Catholic Church at the end of the nineteenth century. Theological responses to science and new philosophical challenges appeared increasingly anachronistic. The ordinary religious response to the accusation of anachronism is an even more drastic effort to promote anachronisms; and this is precisely how the twentieth-century separation of Catholic traditionalism from the mainstream of Catholic theology began. When one looks back to periods of high intellectual activity, such as the 1840s and 50s in Germany, with people like Franz Anton von Staudenmaier and Johannes von Kuhn, one can see that Thomas Aquinas was revered, not as a source of ultimate truth, but as an interlocutor with whom one can disagree. While it is deplorable that just two centuries later, we have fallen back into retrograde views on scholastic theology, nobody should let American traditionalists pretend that this is the normal state of Catholic theology. Thomas Aquinas would never have limited philosophical insights to authority.

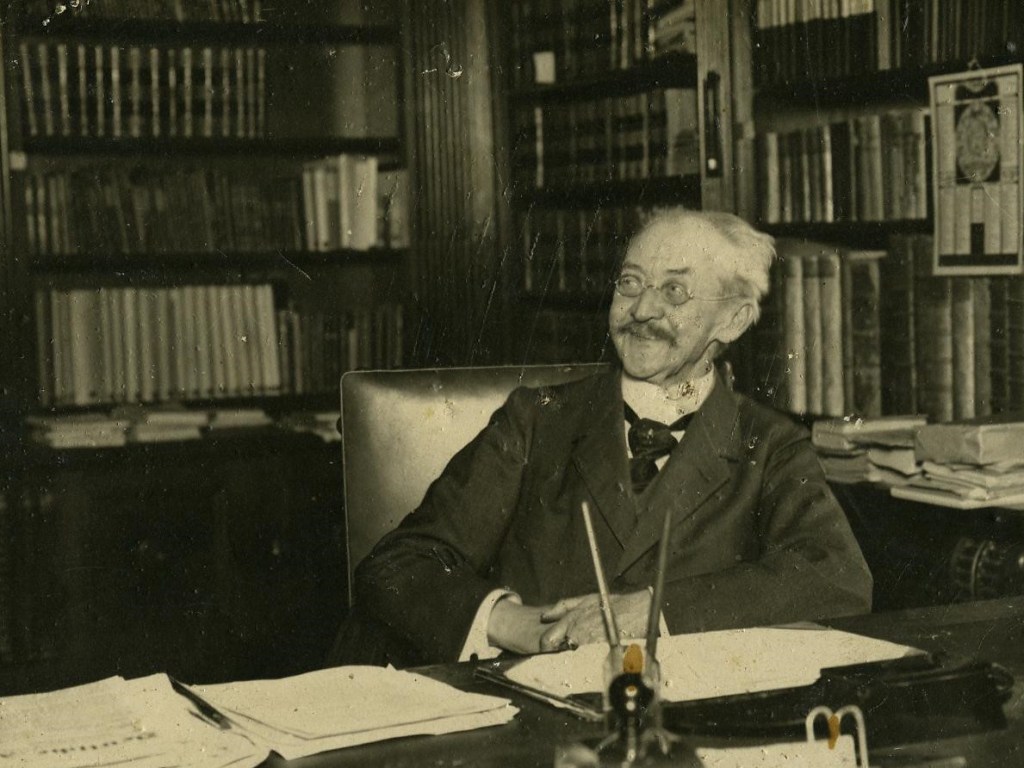

The tradition on which traditionalism insists is an invention–not even a Catholic one, but a cultural invention. It is the desire of people who cannot decide between the political dream of imposing their fantasized, culturally tainted image of religion to the modern world–a world that has become completely incompatible with that image–and the impulse to practice Christian religion authentically. Christian authenticity requires that one prefers other people’s advantage to one’s own. That means that, in every situation in which one desires a certain thing, one must relativize that desire. But the temptation to transform one’s own desires, one’s “comfort zone,” into the desires of a group, and those desires into a “tradition,” is always lingering. Traditionalists give into to that temptation. They want their cultural identity to become universal. Their version of Christianity is their culture. What Harnack said about Chateaubriand may be said about them, and describe them even better: “He thought that he was a true Catholic, while as a matter of fact he was only standing before the ancient ruin of the Church and exclaiming: ‘How beautiful!’”

Leave a comment