In a 2021 interview, Ian MacKaye, the frontman of the hardcore band Minor Threat, explained that the “straight edge” lifestyle—consisting in the rejection of drugs, alcohol, and other excesses—was initially based on practical considerations rather than rigid moral prescriptions. And indeed, MacKaye proclaims in the song “Out of Step”: “This is no set of rules, I’m not telling you what to do.” Straight edge was not meant to be an ideology but a tool to to think rationally and to keep one’s thoughts free from negative influences. It is a response to the temptation of “experiment[ing] with your mind,” in the words of a song by Youth of Today, and of thinking that one can find easy shortcuts to a pleasant and comfortable life, without moral engagement and efforts. Straight edge is a form of anti-experimental quest for lucidity and rectitude.

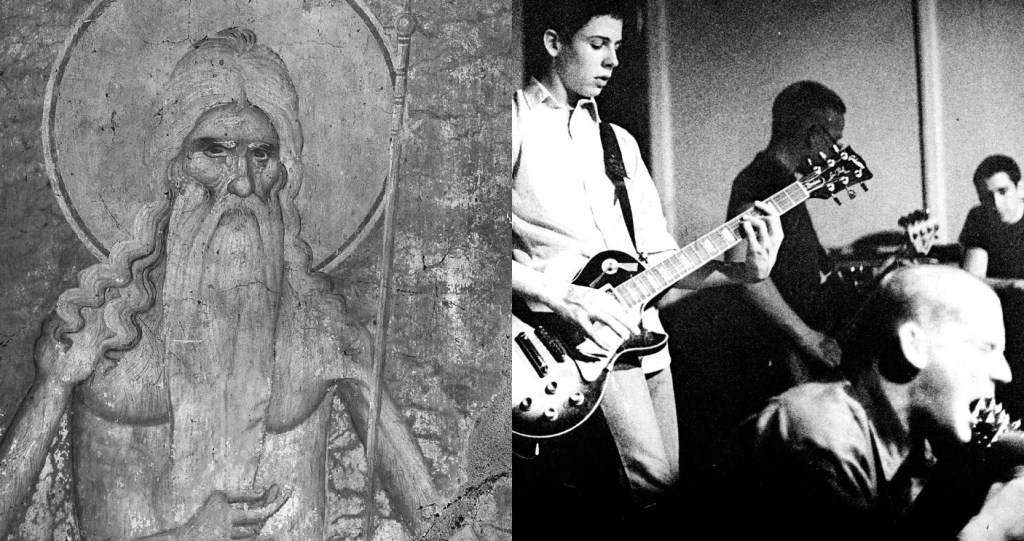

The idea of practicing a sober lifestyle in order to think straight is, however, much older than hardcore. This idea can be found–not just analogically but verbatim–in the literature of the so-called “Desert Fathers,” early Christian monks who inhabited monasteries and hermitages in the deserts of Egypt and Palestine.

Macarius of Egypt thinks that monks should be “fighting with their intellect” (νοῒ ἀγωνιζόμενοι) and use “straight thinking” (ὀρθῷ φρονήματι) to oppose temptations of wrongdoing and thoughtlessness. Maximus Confessor thinks that one should aim to “set oneself straight, through practice, to attain virtue” (τάς ἀρετάς…κατορθοῦμεν διά τῆς πράξεως). The greatest of the theorists of monastic life, Evagrius Ponticus, thinks that once one should seek to “put the mind in a position where it cannot be shaken” (ἀκλόνον τὴν τάξιν τοῦ νοῦ κατασκευάζει). These ancient monks were convinced that everything that one does should be done “straight” (ὀρθῶς, passim in Evagrius)–with a clear mind and in a justifiable way.

The Desert Fathers saw in the attainment of sobriety (νῆψις) one of the main aims of monastic practice. To embrace sobriety is to follow the injunction in the First Letter of Peter, “be sober and watch out” (νήψατε, γρηγορήσατε). Sobriety is opposed to the spontaneous desires and movements of the soul and the body. By thinking straight, one becomes able to see through these movements and to discern whether they are detrimental to oneself and others, or beneficial. When the body is affected by desire, when the soul is affected by anger, hate, or vindictiveness, the exercise of sobriety and straight thinking uncovers the mechanism underlying these affections. By discerning the mechanism, one becomes able to overcome it.

Both in hardcore lyrics and “neptic” literature, thinking straight emerges as a possible response to people who are convinced that some bodily means, some experience, or the consumption of some substance is necessary to expand one’s mind, and that without these things, life remains empty. In the words of the Youth of Today song quoted at the beginning:

“Experiment with your mind

You see things I can’t see

Well no thanks, friend

…

My mind is free to think and see

Strong enough to resist temptation.”

The mind does not need, the Desert Fathers and Youth of Today argue, drugs or other experiments to attain knowledge about itself and its environment. The tool to attain that knowledge comes from rational self-determination.

The deep ideological and linguistic parallelisms between the two traditions are odd. Hardcore music has traditionally been skeptical against religion, if not straightforwardly anti-religious. Some of the most important hardcore bands in the straight edge movement called out religion as one of the motors of bigotry and political violence in the world: SSD, DYS, Uniform Choice, and other bands. The alliance between right-wing politics and religious conservatism seems to act as a unifying cause for hardcore’s opposition to religion.

However, the roots of this opposition are more complex than one would think. The arguments made in hardcore lyrics against religion tend to emerge from the perception of what religion is doing with people in the present world. And it is evident that the visible aspects of religion are, in the modern West, deeply repulsive. Religious conservatism is responsible for hate crimes against LGBTQ+ groups and people, for the erasure of cultural identities, for opposition against healthcare for pregnant women, for racism and misogyny, and more generally, for moral corruption, exploitation, and hate. These issues constitute some of the most urgent and acute problems of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. In the face of these problems, there is no doubt that hardcore’s rebellion against religion has its roots in reality, and not just in abstractions or preconceptions.

However, the fact that in the history of hardcore music, various bands and musicians shifted toward Eastern religions such as Buddhism and Hinduism suggests that the role of religion is more ambivalent. It seems that, in the quest to find an intellectual and political paradigm that does not contradict hardcore’s commitment to oppose injustice and oppression, some bands sought to overcome the traditional aversion to religion, going so far as to draw on religious sources. One might be tempted to argue that the way that hardcore musicians adopted Buddhist and Hindu ideas is tainted by Western categories and the inculturation of these ideas in the Western mind. But the shift toward religion shows that hardcore deals with religious views in a more nuanced way than advocates of cultural conservatism like to think.

The profound affinities between the Desert Fathers, as a religious phenomenon, and straight edge can only be justly appreciated against this background. Neptic literature is an expression of an uncompromising, radical, and spiritual interpretation of the New Testament. The Desert Fathers sought, not to adjust the ideas contained in the New Testament to their lifestyle and cultural standards, but, on the contrary, to adjust their own life to these ideas. This adjustment and the radicalism that it requires cannot be said to be typical for Christianity, and the baneful entanglement of religion in politics that took place in the late fourth century showed how fragile it was. But it is precisely the marginality and boundary-challenging quality of the Desert Fathers’ spiritual intransigence that make them comparable to hardcore musicians. Both movements agree to the idea that one simply does not make compromises with the world, even if there is a promise of comfort or new experiences.

Perhaps one could say that hardcore music and straight edge are what today’s Christianity needs to recover its original enthusiasm and boldness. Christians today, both in the US and Europe, and widely and blatantly rejecting the neptic call, as uttered by Paphnutius of Thebes, to “walk straight on the path to God” (ὀρθοποδεῖς εἰς τὴν ὁδὸν τοῦ Θεοῦ). They are attracted by the crooked path of cultural and political conservatism and refuse to acknowledge the contradiction between neofascist ideals and the ideals articulated in the New Testament. They become servants of political programs that aim to achieve the contrary of the eschatological vision that Christianity projects for humanity. They become, in the words of an SSD song, “tame” and dull subjects, instead of men and women possessing the “boldness” (παρρησία) praised by the Desert Fathers:

I can’t explain

Drugs can’t help

They make you tame

When you gonna realize?

(SSD – “Fight Them”)

Leave a comment