Est enim mentibus hominum ueri boni naturaliter inserta cupiditas, sed ad falsa deuius error abducit.

“The human mind is inhabited by the natural desire of the true good–but a devious error leads it astray, to falseness.”

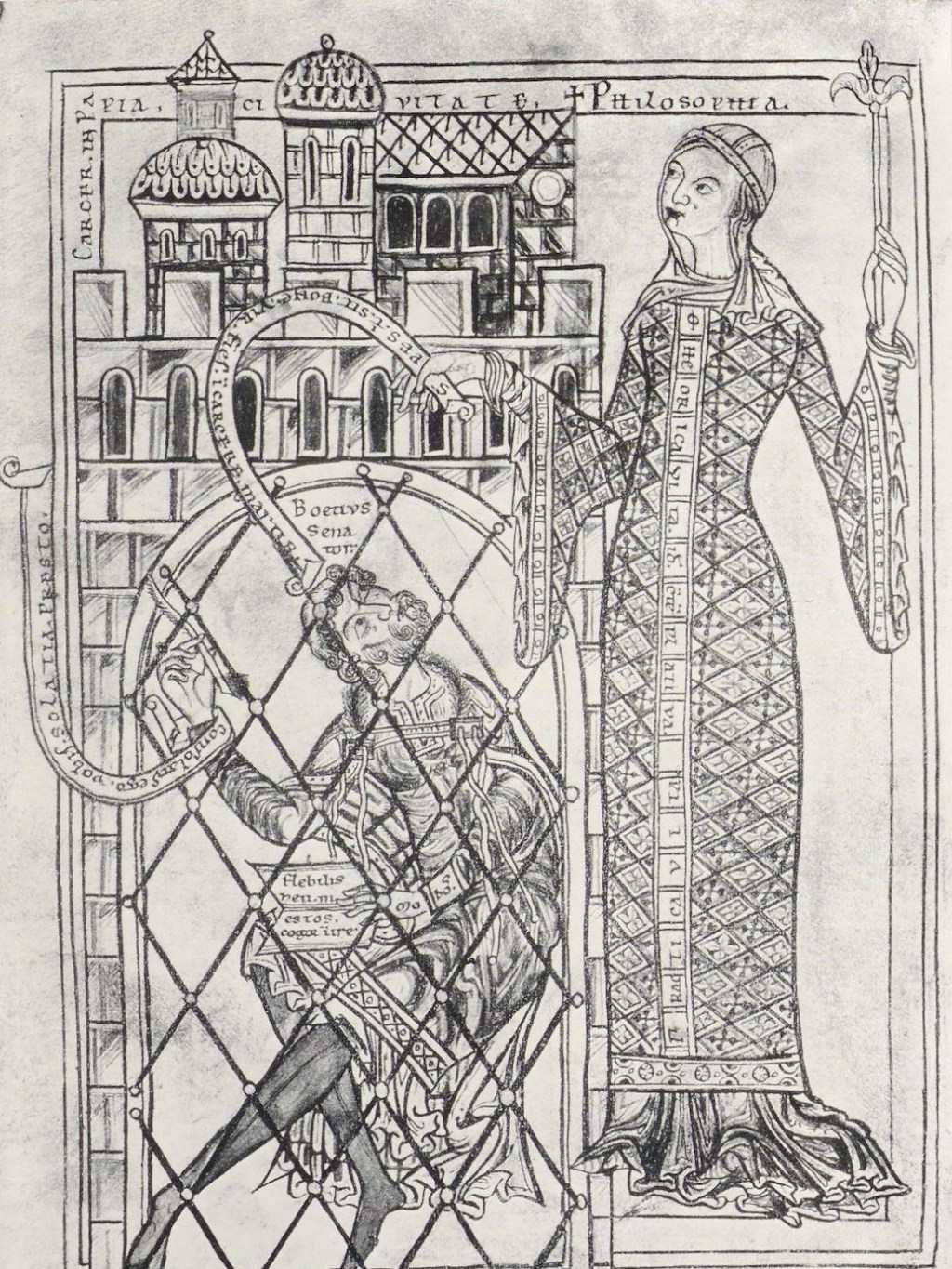

(Boethius, De consolatione philosophiae III, 2)

One of the twenty-first century’s defining intellectual achievements is its demand for moral accountability. This accountability does not just apply to the present but extends, to a certain degree, to history. Philosophers, for example, have acknowledged that one cannot mention Heidegger’s philosophy without mentioning his Nazism, his cowardly behavior toward his colleagues, and the strong links between his thought and the environment from which Nazism emerged. Being committed to finding concepts that apply to reality as such, or that have a universal scope, philosophers must—if they truly believe that their concepts apply to everything—draw consequences for their own lives. If they don’t, their ideas are disavowed.

In 1977, the Affaire de Versailles shook France’s intellectual milieus. Three 40- to 50-year-old French men were summoned to court in Yvelines, near Versailles, in a case of sexual offenses and indecency. The offenses concerned children—girls between 13 and 14 years—and were described as minor, i.e., not involving rape or violence. On the day before the beginning of the trial, the French journal Le Monde published a letter calling the judge and persecutors to set the three sexual offenders free immediately. The reasoning of the letter was that the men had already been detained for three years, and that three years were a punishment sufficient for such a minor offense.

The letter criticized that society had evolved and now “is ready to acknowledge that children and youths have their own sexual life—why would a thirteen-year-old girl otherwise be allowed to take the pill? [sic]” (tend à reconnaître chez les enfants et les adolescents l’existence d’une vie sexuelle (si une fille de treize ans a droit à la pilule, c’est pour quoi faire) ?) The argument is that, if girls—the letter is written from the standpoint of adult men—are allowed to determine their own sexuality, it is incoherent to represent their possible partners as criminals.

For contemporary readers, the content of the letter is unendurable—for several reasons. To our sensibility, it seems obvious that it is wrong to infer the right to sexual relations with children from the universal right to sexual autonomy. Sexual predation exists because autonomous subjects can be influenced and manipulated. Even more disturbingly, the letter is written specifically from the perspective of an adult man seeking intercourse with underage girls. It gives itself the appearance of an apology of sexual self-determination, but its tone, as well as Gabriel Matzneff’s follow-up letter “L’amour est-il un crime?” (“Is love a crime?”), leaves no doubt that the authors make a specific case for the right of adult men to seek intercourse with underage girls. It is impossible to read the letter and not be unsettled by the fact that it was, in fact, written and published less than 50 years ago.

The letter was authored and signed by several dozens of French intellectuals, among which one finds Roland Barthes, Jean-François Lyotard, Jean-Paul Sartre, Félix Guattari, and Gilles Deleuze as well as his wife Fanny Deleuze. The three incriminated men were condemned to prison sentences between 5 to 10 years. One of the three men, Bernard Dejager, was indicted again in 2018, at 89 years, for the possession of child pornography, making it obvious that the case had never been about consent or self-determination.

Later in the same year, a similar group of people wrote a letter calling for legal changes regarding the “right” of children to make their own sexual choices. In a vastly inappropriate language, the authors see the laws prohibiting adults to approach children as a form of “strict segregation” (ségrégation minutieuse) that does not observe the “right” (droit) of children to accept such approaches. They proclaim: “It is a social problem.” (C’est là un problème de société.) Similarly to the first text, this letter employs disturbing logic and shocking analogies involving the sexual life of children. This letter was signed, among others, by Louis Althusser, Michael Foucault, and again, Gilles Deleuze.

It is worth pursuing the background to Deleuze’s support of the two letters. His work exemplifies the propensities of French philosophy in the 1960s and 70s to moral transgression, and the disturbing tendency to give that transgression a philosophical appearance.

Deleuze wrote extensively on Leopold von Sacher-Masoch and the Marquis de Sade, and praised them, in his Le froid et le cruel, for practicing a type of literature that does not “express the world” (nommer le monde) but is “capable of absorbing its violence and excess” (capable d’en receuillir la violence et l’excès)—ideas that he took from George Bataille’s reading of de Sade. This form of excess is not something punctual, Deleuze thinks, but a “twin” (double) of our own reality, underlying our history with the same continuity, but in a perverse and distorted form. He speculates, with de Sade, about a primal nature “above laws and rules” (au-dessus des règnes et des lois), connected to a “primordial chaos” that awaits to be unchained. One is left to wonder about the scope of Deleuze’s words—if they were an exegetical commentary, or a statement about the categories of human existence. In the former case, and under the assumption that Deleuze spoke only about the abstract notion of “laws,” one is still left to wonder whether Deleuze’s vision of how sexuality could be socially regulated was essentially different from this literary projection. In the latter case, it seems evident where Deleuze’s support to the three incriminated men came from.

Seeing that Deleuze’s tends to challenge established intellectual and moral norms, one would think that he thought of the basic categories underlying these norms critically, too. For why would one reject legal frameworks regulating sexuality without questioning their conceptual, ideological, and historical basis? One would expect Deleuze to challenge philosophical conventions and destabilize the narrative of Western philosophy.—But rather than overcoming the Western foundational myths of philosophy, Deleuze justifies it. Deleuze is, along with other French philosophers such as Jacques Derrida, one of the most vehement and unapologetic advocates of philosophical eurocentrism and xenophobia.

In What is Philosophy?, Deleuze and Guattari state that Indian and Chinese philosophies aren’t actual philosophies, because all they deal with are vertical projections of transcendence. Deleuze thinks that that the great discovery of Western philosophy is immanence. Philosophical concepts are like ripples in the sea, the immanent profile of an ever-shifting reality. Transcendence is an illusory projection that distinguishes religion from real philosophy. Western philosophers have secularized that projection and shown that it is, in fact, a projection, and not a conceptualization of a dimension of reality. It is worth mentioning that Deleuze and Guattari articulate this argument in the late twentieth century, long after it had become clear that the only acceptable paradigm for philosophy is a universal one. Their argument in What is Philosophy? is consciously reactive and retrograde.

It is a strange phenomenon and coincidence that so far, Deleuze’s depraved political activism, his impossible ideas on the sexuality of children and youths, his praise of sadism and masochism, his eurocentrism, and his xenophobia, haven’t contributed to curving or attenuating philosophers’ and young students’ interest in his work. Deleuze’s writing and political activity suggest that he was a sexual predator with pedophile tendencies, and a xenophobic apologist of Western superiority. Why do philosophers continue engaging his work?

The Anglo-American myth of “continental philosophy” as a distinct tradition in the history of philosophy and of French Theory as a haven of philosophical postmodernism have covered the human reality of the French philosophical milieu in the 1960s and 70s with an aura of originality, literary genius, and opposition to traditions with ideological commitments. Most notably, Deleuze, Guattari, Derrida, Barthes, and Sartre are credited with the overturning of substance metaphysics, appeals to transcendence, idealizations of premodern philosophies, and religious—Christian—influences on philosophical worldviews. Deleuze and Derrida call for metaphysics of difference, the deconstruction of transcendence, the overcoming of academic philosophy’s commitment to a linear vision of the history of philosophy, and secularization of religious concepts.

These ideas resonate with the fundamental elements of contemporary critical agendas: diversity, tackling of cultural hegemony, deconstruction of historically linear narratives, opposition to essentialist philosophies. And yet, what appears as a correspondence here is, in fact, a case of homonymy. Deleuze did not plead for boundary-challenging difference, but for difference within a strictly Western framework; he did not attempt to overcome religious influences and covertly substantialist and essentialist visions of the human being to replace them with a new, uncommitted vision, but to promote what he considered to be the delirious, chaotic, excessive first nature of the human being; he did not see philosophy as a tool to modernize societies and politics but as an aposteriori justification for his personal aspirations and desires.

Late twentieth-century French philosophy is not an ally of modernity. The philosophical exceptionalism that has brought suspicions upon Hegel, medieval philosophy, ancient philosophy, Christian theology, and other traditions, and that maintains the idea that Deleuze may be read as an unproblematic philosopher, as if he had existed as the mere embodiment of his philosophy, is unwarranted. It is morally unjustifiable to read Deleuze and to reject the history of philosophy for critical reasons.

Philosophers must be held accountable for what they said and did. They must be held accountable for the transgressions and errors that they committed consciously and reactively. Deleuze’s defense of pedophilia and xenophobia is not a generalizable manifestation of his cultural environment. It was Deleuze’s and the other philosophers’ active choice to commit themselves to this defense. If twenty-first century philosophy commits itself to creating and safeguarding spaces for voices that have been silenced in the past, to express oppression and revolt, then it is necessary to hold philosophers who have endangered that space accountable for their behavior.

Philosophy sets high moral standards. It is time to toss Deleuze aside and read Boethius—Boethius, who died knowing that if an idea is not followed by an appropriate deed, the idea was worth nothing: “One who fails to do good can’t rightly be called good.” (neque enim bonus ultra iure uocabitur qui careat bono, de cons. phil. IV 3)

Leave a comment