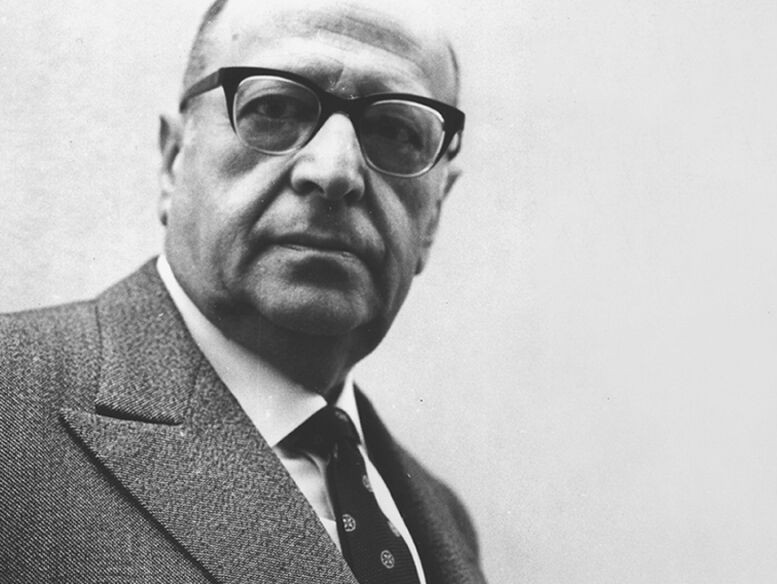

Max Horkheimer famously defined the social function of philosophy as a “critique of the establishment” (“Die gesellschaftliche Funktion der Philosophie,” GS 4, 332–351, 344: “Die wahre gesellschaftliche Funktion der Philosophie liegt in der Kritik des Bestehenden.”). Philosophy critiques established truth claims by revealing their immanent failures and by pushing philosophers to overcome them.

But is it really so? Did philosophy not often produce reactive theories, prohibiting innovative ideas rather than promoting them? Is philosophy not part of the “Western tradition,” claimed by cultural conservatives as a tool for identity politics? Doesn’t philosophy buttress ideology?

There is more to Horkheimer’s definition. Even when philosophy seemed to fall short of its critical function and instead support ideas that contradict lived experience and social reality, it did so in opposition to the illusion — or, as Wilfrid Sellars calls it, the “myth” — that there is a “given” reality exempt from critique. There is no “given,” and philosophy serves to critique appeals to the imagined “given.”

Plato’s metaphysics do culminate in the affirmation of a suprasensible realm of ideal realities — but they also ask us to not trust any visible realities or appearances, precisely because appearances do not withstand critique. Neoplatonists do engage in religious speculation about the nature of the gods and the essence of the cosmos — but they do in reaction to irrationality and superstition, intending to demonstrate that late ancient Greek religion is not just an empty mythological and ritualistic tradition. Thomas Aquinas did work toward proving that Christianity is an all-encompassing, universally true explanation of everything — but he did so specifically to overcome inarticulate, supernaturalistic claims falling short of justification, even as he was threatened by religious authorities. Descartes did consider the idea of God as the only bulwark against error — but his argument aims to destroy naturalistic claims about the origin and justification of knowledge. Rudolf Bultmann did found his existentialism on the person of Jesus — but he sought to oppose philosophies and religious views that attempted to either claim that religion has no bearing in philosophy, or to infer the truth of Christianity from the natural state of things.

At each historical step, philosophy reacts to established claims: either to show that, even if these claims are grounded in authoritative statements, they require justification; or to expose the inadequacy of those claims and to propose new forms of knowledge. It confronts established truths with the implacable mechanism of categorization, rationalization, and systematization. If the claims conform to this mechanism, philosophy affirms their validity. If they withstand it, philosophy uses their falseness to dialectically rise to a higher perspective.

If categorization, rationalization, and systematization are the criteria of philosophical critique, fascism may be seen as the demented, irrational, and non-conceptual attempt to withstand critique, and to present the establishment as immune to critique.

The mechanism of fascism is the death of philosophy; or to put it differently, philosophy goes to the opposite of fascism. Fascism promotes a non-dialectical understanding of established truth claims. To fascists, the establishment — a culture, a national tradition, political hegemony — is a primordial fact that must be preserved through self-affirmation. But fascist self-affirmation is not Hegelian. It does not proceed through dialectical self-differentiation. A fascist system does not reckon the autonomy or validity of any system different from itself. Rather, fascist systems affirm themselves by invoking the looming threat of some imagined form of the “other” — the alleged enemy. The enemy is not a real thing, or person, or group. It is an image projected on things and people to ground collective self-affirmation in the rejection of a negative counterpart. Fascists preserve their system by calling for the destruction of that which allegedly negates them. They achieve self-affirmation without self-negation.

By contrast, the dialectical impetus of philosophy is open and non-exclusive. It does not proceed by projecting otherness and negating it. It constantly refers, through the critique of the establishment, to the “other” as something real, irreducible to the rules of the establishment. Philosophy is fundamentally inclusive in that it finds its truth in negating its own assumptions rather than the “other.” The “other” is, for philosophers, the element or person from which truth arises. Fascism on the other hand is animalistic. It self-preservation is violent and requires the death of the other. Its impetus is exclusivist: the fascist system must triumph and asphyxiate any reality that withstands its claim to absoluteness.

Extending Horkheimer’s definition, one could see philosophy as a form of anti-fascist revolt. Whenever a political system stifles intellectual curiosity, whenever it disavows reason, bullying those who uphold rationality as the ultimate source of validity, whenever it uses defamatory names and labels to expose inquiries into its constitution as illegitimate or hostile, it generates fascism. The dynamic against which that generation must fight is philosophy, precisely because it is philosophy that justifies curiosity, reason, and critique as ultimate means of knowledge. Hence, the philosopher is naturally anti-fascist, and philosophy is anti-fascism.

Fascism likes to wear the mask of the enemy that it perceives as a threat to its subsistence. It engages in what Adorno calls “mimesis” (Dialektik der Aufklärung, 194 et passim), in hysteric imitation and simulacra, frenetically attempting to enact the enemy that it needs to negate. Mimetic fascism imitates philosophy by affirming that philosophy is the root of “Western civilization” and that its sources must be preserved. The “great books” of philosophy, Plato, Aristotle, Descartes, must be read as testimonies to the threatened spirit of the West. Western education, paideia, is threatened by the “other,” that which has no gender, or a different gender, no religion, or a different religion, and it must destroy the other to maintain itself.

Under the influence of fascism, philosophy can turn into an ideological tool. When philosophers do not openly commit to critique, dialectical self-negation, and inclusion, they become a danger to societies. They forget that it is forbidden for them to present a certain tradition as true or inherently superior to any other tradition. The force of philosophy lies in its capacity to overcome itself. When philosophers agree to affirm the establishment instead, they open the door to the claim that what is established is true and must be preserved, thus transforming the philosophical logic of critique into a logic of glorification.

Perhaps philosophers have never been able to reach consensus on a single statement or idea, not even with regard to what philosophy is, or what it should do. But perhaps anti-fascism is such a non-negotiable consensus. It is not a rule, or an axiom, or related to any specific content or methodology. Rather, it is the origin from which any metaphysical, ethical, linguistic, or logical question arises: the intuition that a given concept or theory is insufficient, or that it lacks justification, and that its insufficiency can be proven, or that a justification for its sufficiency can be given. Critiquing the established norm, challenging the authority that has established it, and generally rejecting any kind of authoritative intervention is something that no philosopher could possibly contest, lest they forfeit their own function and vocation.

Philosophy is anti-fascism. When it is asked to approve, it negates. When it is mobilized, it resists. When it is attacked, it speaks out.

Leave a comment